|

ASPR NEWSLETTERThe American Society for Psychical Research, Inc. |

The following article is based on a lecture presented by Montague Ullman, M.D., at the "Exceptional Human Experiences" conference held in New York City, June 13, 1993. It was published in the ASPR Newsletter. The Newsletter was published from 1968 to 1996. Articles can be viewed in the ASPR library. Certain past issues are available for sale. Please inquire as to availability.

Dreams are ordinary only in the sense that everyone has them. What makes them extraordinary and qualifies them as exceptional human experience are the gifts they bring to our lives if we learn how to receive them. I'd like to share with you the way I think about dreams and their importance, and then suggest answers to three questions. What is ordinary about our dreams? That's an easy question. Two, what is extraordinary? That's not so easy. Three, what defines dreams as exceptional human experiences? That's the one I think I'd like to explore with you.

Let me share with you my ideas about dreams, which are not necessarily the prevailing ideas about dreams, because they are outside of the orthodox psychoanalytic tradition. Dreaming and the dream refer to two different, though closely related, events. Dreaming is an intrinsic part of the sleep cycle that recurs every 90 minutes during the night and is associated with distinct psychological changes that signify a state of arousal of the organism. The dream, in contrast to dreaming, is a remembrance in an awake state of whatever it is that we can bring back from the previous night's dreaming experience. These two modes of consciousness resort to two different languages to say different things about the same organism. To understand the dream, we must begin with an understanding of the way the two languages differ and what it is we're saying when we speak the language of the dream. Our two languages appear to have evolved as a way of speaking to each other.

Let me begin with waking language. Waking language appears to have evolved as a way of speaking to each other about the world and the way we experience ourselves in the world. The world is broken down into manageable and agreed upon categories, which can then be communicated hrough a structured grammar and which can convey in a logical manner how our experiences are organized in space and time. Language is a way of categorizing reality so as to be able to talk about our experiences. It's actually a deeply rooted way of making reality more discrete than it really is.

But our needs go beyond what can be transmitted in this fashion through language. We seem to need a more direct way to encounter and express the impact upon us of the world we live in. We need a more effective language for the expression of feelings. In waking life, to accomplish this we resort to the language of the arts, the language of music, the language of poetry. While asleep and dreaming, a pictorial figurative sensory language takes over and reflects our feeling states. The dream language has more in common with the language of the poet than the language of the scientist. Both the poet and the dreamer rely on metaphor for its expressive effect. There are, however, at least three significant differences in the way that the poet and the dreamer use metaphor. The poet rearranges words to create the metaphorical quality, or the words that best convey the feeling that he or she wishes to communicate to others. The dreamer shapes images and pictures into metaphorical statements. The poet addresses an audience outside himself or herself. The dream is a private message to oneself. Finally, writing poetry is a task of greater or lesser difficulty.

Dreaming and the creation of these visual metaphors that happen to us through no deliberate or volitional effort on our part is easy; all we do is go to sleep. The neophyte in dream work has to learn to look at the images, not as photographic replications of reality, but as metaphorical ways of conveying the felt nature of the predicament of the dreamer at the time the dream occurs. We have adapted, in what in all likelihood is a primitive imaging capacity, which we probably share with animals lower in the evolutionary scale, and we've learned how to use it to serve as an instrument for symbolic, rather than literal, expression. Our sleeping self is concerned with managing residual feelings that stay with us until the time we go to sleep and that surface at the onset of the dream. Metaphorical imagery is a most suitable, symbolic vehicle for containing and conveying feelings, just as it does in poetry. A man who pictures himself, for example, driving down a steep hill in his dream and having his brakes suddenly fail, will experience the sensation of being in an uncontrollably dangerous life-threatening situation. He will experience this sensation far more powerfully than if, in waking life, he thinks something is disturbing him. He is not clear about it but the dream examines and explores the depth of that disturbance and confronts the dreamer with the reality of it. In the dream, we are part of the metaphor we, ourselves, are creating, a fact which places us in an immediate relationship to the feelings being generated. We are the actors, not the reporters of the scene that is taking place. There is no way out of the dream, except through the termination of the dream, either by the generation of feelings strong enough to awaken us, or by somehow resolving the issue, at least temporarily, so that there is a natural passage back into dreamless sleep.

The concept of the visual metaphor is basic to dream work, and its importance cannot be overly stressed. We have been expressing our personal poetry in dreams, in a language we've been using since childhood, and yet it continues to feel strange and unfamiliar to us. To understand this fully, we must also take into account the unique content of our dreams. What is it that's being expressed through this language? When we use pictorial language, what are we saying that makes the dream so potentially illuminating when we are awake? Our imaging capacity provides the form that our consciousness takes, but where does the content come from?

As we fall asleep, we close off our input channels. We close ourselves off to the sensory stimuli coming at us from the outside, with a few notable exceptions. For the most part, no new information is coming into our system, so that whatever we become conscious of during this period of dreaming has its origin sometime before falling asleep. Freud spoke of the day residue as the starting point of the dream. A recent event sets up a lingering tension that surfaces at the onset of a dreaming period and acts as a shaping influence on the content to be developed. What gives this recent residual feeling its extraordinary power to do this lies in the fact that regardless of how trivial or insignificant it may seem at the time, it connects with unsolved, unresolved issues from our past. We're not aware of this connection. Asleep, it comes clearly into view. Our dream may open with a childhood scene in the house we grew up in, when we were five or six or whatever. The first important point then is that the dream starts in the present. The issue it addresses derives from our past, but continues to be of some importance to us in the present. No one of us grows up perfect in this world, and we're all working and reworking residual issues and tensions from our past.

What we do with this residue while dreaming is quite extraordinary, as judged by waking standards. We seem to do many things at once. We scan our entire life history for events and experiences that are emotionally related to it. We explore our past ways of coping with whatever vulnerable areas have been exposed, and we mobilize the resources at our disposal to come to some resolution. In short, while dreaming we are reassessing the significance of recent events in the context of the past. We take a historical perspective on our own lives. That is not easy to do awake, and in a rather clever way we express it all through pictorial metaphors that highlight the feeling tones evoked in the course of this self-exploratory adventure. It is all done effortlessly and seemingly instantaneously. We have brought a current residue into relationship to past feeling residues. In so doing we bring together important information relevant to whatever it is we're struggling with now. So, that's the second important thing about dreams. The first is, it has a current meaning to us. It starts with where we are now. The second is, it gathers more relevant information from our past in its relationship to the present. That brings us to the third and, in my opinion, most interesting and important quality of our dreaming life, particularly in its relationship to the question of the healing potential of these images. While asleep, we are alone and perhaps more alone than at any other time in our life. We have temporarily disconnected from the world around us. We have temporarily suspended our social role and our social facade. We don't need it when we're asleep and dreaming and not acting in the world. We no longer need our social defenses, those various ways of protecting ourselves from truths we do not wish to reveal or cannot see at the time. In the act of going to sleep we undress not only physically but psychically as well. When our brain gets a signal to start dreaming, there we are in our emotional nudity.

What happens next is best described by analogy. There is a magical mirror in this place we find ourselves while dreaming. It is a mirror capable of reflecting a profoundly honest picture of who we are rather than who we would like to think we are or who we would like others to think we are. Another bit of magic in that mirror is that it is there for the dreamer only. No one else can look into it. Being alone and confronted with a mirror that provides a private view of the dreamer, the dreamer risks looking into it, himself or herself. The view reflected back is the view rendered by the imagery developed in the dream. It is a view without pretense. It is the truth, as close as we can get to whatever we mean by subjective truth. In a sense it is a privileged portrait of intrinsic value to a dreamer in search of a more honest self-concept.

For the most part, our dreams are not understood or appreciated in their individual and social significance, and we are largely unaware both of the personal and social opportunities offered in our dream life. Once awake there is an overwhelming tendency to slip back into a familiar and well-known character structure and ordinary behavior. In short, our dreams offer us a spontaneously generated visual drama, depicting where we are subjectively at the moment. They help us understand the connection of the present to the past as we move into the future. It isn't just a free-wheeling exercise for the fun of it. We are all moving into a future, which is not known for a certainty. We know certain aspects of it, but our dream fortifies our movement into this future by preparing us in terms of connecting our current past and present. Our dreams resort to a variety of techniques to call attention to aspects of ourselves we are simply not attending to or not attending to enough, or not attending to clearly. They frighten, shame, ridicule, exaggerate, and at times expose wondrous feelings that we never knew we had, all of which offer us the opportunity to get to know ourselves better.

What is ordinary about dreams? Well, everyone can answer that question. They are everyday or more exactly every night occurrences. They are universal. They range across all ages and all cultures, present and past. There are very common dreams that most of us have had at some time in our life. We find ourselves flying or falling or having our teeth fall out or wanting to move and not being able to, and so on. The problem is that they are so ordinary that their extraordinary features are overlooked. Let's look at some of those extraordinary features.

The first one I want to look at is dreaming consciousness as producing potentially healing imagery, or the connection of dreaming to healing. The imagery we create at night has a potentially healing significance for us. The special features of dream images that relate to this healing is the way they link our present concerns to its roots in the past and the honesty with which they confront us with our own true feeling. When you consider that statement, it really has to do with whatever it is that psychotherapists do to make us whole. They start with where the patient is at the moment. They start with a concern with the connection of the present with the past and presumably they can offer the patient a more honest perspective on what is going on than the patient had originally. We have that kind of built-in potential capacity in our dreams, only we don't know it, and because we don't know it, unfortunately, we foolishly give dreams a very low priority in our culture. So called primitive cultures are a little bit wiser about that and give the dream a much higher priority.

Dreams exert their healing potential, in my opinion, by their capacity to portray the state of our connectedness with others and with ourselves at the time. I think that's the essence of what we're concerned with. Our dreams seem to zero in on whatever has occurred that affects these connections and has not clearly risen up to waking consciousness. Anything that impinges on these connections, either in a good or in a bad way, as a consequence of recent experience, becomes a focal point of a dream. On the good side, there are experiences that reinforce or expose positive qualities in us that we lose sight of. The innocence and curiosity of a child, as well as aspects of our own creativity. On the other hand, we are sensitive to anything going on in our life that corrupts, corrodes, or threatens to destroy or fragment our connectedness to ourself and to others. I have been referring to dreams as potential healing experiences, because for that healing experience to occur, we have to allow the confrontation to take place between what the dream has to say and our ordinary waking view of ourselves. That is the rub. Dreams are creatures of the night. If we're fortunate enough to be able to relate insightfully on awakening to the story they're telling, then to that extent, some degree of emotional healing can take place. We are more in touch with ourselves. More often it takes a more rigorous socializing process to get a dream to yield its secret, and this involves a helping agency, one that can provide a safe haven in which to explore the dream, and one that has the knowledge and skill it takes to make the exploration effective. Nine-tenths of my psychoanalytic colleagues will not agree with me, but the knowledge and skill involved in dream work can be conceptualized and taught to any dreamer, and that means anyone. Skills are involved, but people can learn these skills through experience if they know what they're trying to do, and if someone can orient them, at least conceptually, to what the nature of the skill is. A violin teacher can tell a student how to put the bow on the violin, but the student has to practice the skill of how to use that bow.

For the past several decades, my life has been divided into three parts. At first, I was a psychoanalyst, for a third of my professional life. Then, I was a community psychiatrist, interested in moving mental health strategies out into the community. For the past two decades, I've been involved in developing dream-sharing groups. I've considered and explored how people can get together to engage in what I think is a socially unmet need to come together in a safe environment to explore through dreams deeper aspects of their being, to make discoveries that help them to unload secrets that interfere with their connectedness with other people. I think everyone needs that, but not everyone needs therapy. And so, dream work, serious and effective dream work, as far as I'm concerned should extend beyond the boundaries of the consulting room and reach out into the community, I believe Bill Stimpson had this same idea many years ago and was the first editor of the Dream Network Bulletin, in an effort to call to the attention of the general public, the creativity, the healing potential, and the social value of our dreams. Well, that's one extraordinary feature of our dreams.

Another one is the question of the creativity in our dreams. While we are dreaming, we are in the metaphor-manufacturing business. The metaphors we create are visual in character, generally, although any sensory modality can be involved. They are highly idiosyncratic in nature, in contrast to waking speech, which is full of consensual, dead metaphors. In that sentence there are two dead metaphors. Full has a physical connotation. A container is either full or empty. Dead is a word we use in relation to living organisms as in alive or dead. Our waking language is metaphorically full of such metaphors. In my dream-sharing groups, I've listened to many, many dreams, but regardless of how many dreams I've heard, each new dream is a unique experience in the art, and I call it an art, definitely, of crafting meaningful, visual metaphors. There also is an art to doing dream work as we seek to help the dreamer bridge the gap between image and reality and thus capture the felt meaning of the metaphor. Over and over again, I've had the impression, after we've worked through a dream in a group, that no matter how short that dream may be, even a tiny fragment, it still presents us in a holographic way with significant connections between past and present that have never been completely realized, conceptualized, or fully conscious. If we had set out to do so, even if we were Michelangelo or Rembrandt or whoever, we could not deliberately paint a picture in so few images that could capture so much information. This has left me with a feeling that while dreaming we're tapping into a universally shared creative source, available to all of us, a source that creates images that speak elegantly and accurately to our subjective state at the time of the dream. Whether or not we view ourselves as creative in our working lives, our dreaming psyche revels in its own seemingly unlimited creative potential. Catching on to the metaphor in the dream leaves us with an Aha feeling no different from the experience of the aesthetic quality of music, poetry, or any other artistic form of metaphor.

Let me come to a third quality of dreams that we have hardly begun to explore, and that is the fact that dreams, in addition to their personal reference to our lives, contain social references as well. They make reference also to the world, to the life we're leading in a specific society. The issue of connectedness that I referred to in regard to the nature of healing goes beyond the individual and his or her immediate concerns. We are all aware of the toxic fallout from our society in the form of poverty, crime, pollution, the residues of racism, and the generally prevailing level of agony and alienation. What we are not so aware of is how the inequities and fallouts from the institutions and social practices that shape our existence are woven into the unconscious fabric of our lives. To the extent that this occurs, we remain unaware that it is occurring, and we enter into an unconscious collusion with the very forces that so undermine our common humanity. So our dreams speak, in addition to the personal, to our social concerns. What I find remarkable about dream imagery is the ability to depict the way social issues interlock with personal ones and how each one plays into the other in a mutually reinforcing way.

Here are a few examples of what I mean. A woman in her late thirties is about to embark on a new relationship. She senses some hesitancy on her own part, and she has a dream that displays the root of her ambivalence. In the dream, she sees her father sitting on a swing with four female relations, all in their heyday, dressed almost like can-can girls. What emerged from the work on the dream were two powerful images that surfaced from her childhood that continue to influence her approach to a new relationship. One was that of the male, derived from the image of her father, as privileged to flirt and play around with other women. That's what he did. The other, that of the female victimized by the predatory male, as was her mother. These are images she is still struggling with. In a larger sense, they relate to the residues of sexism, a social issue, as yet not fully disposed of. The privileged male and the victimized female are still available social stereotypes that play into our unconscious.

Here's another example, also from a woman. Women gravitate to my dream-sharing groups more than men, in the proportion of about 9:1. Women seem to be more interested than men in their feelings. This next dream also involves sexual stereotypes. Two significant images in the dream, related to this, are that of a wounded bird, who was unable to join the flock in flight, and the other is that it is picked on by a group of arrogant pheasants. You can see the interpretation immediately. The second image is one of a contractor who in reality is involved in remodeling her home. In that dream, he tells the dreamer he can't finish off the basement for repairs, without at the same time finishing the upstairs bedroom. What became clear from the dream work was that there was this unresolved tension between her husband and herself. She had recently gone into therapy with the problem. The dream reveals what therapy was opening her eyes to, namely, the fact that in order to deal with the issues of marriage, the upstairs bedroom, she would also have to deal with the personal problems, the wounded bird, and the disarray in her own basement/bedroom, and that had to do with her submissiveness, her self-deprecatory tendencies, her inclination to accept her husband as the stronger and dominant one. The pheasants, who pick on the wounded bird, were likened by her to a string of older brothers in relation to whom these trends emerge.

I've simply tried to show that the private issue, highlighted in the dream, gains expression by attracting to itself images that are taken from social experience and carry a congruent, social meaning. This generally escapes notice, because we're not in the habit of extrapolating from the image to the social reality that lies beyond. The dreamer pauses nightly to assess these influences, particularly in regard to their capacity to upset any preconditioned, pre-existing equilibrium. Our dreams remind us that we are part of a larger whole, and just as the dreams are carriers of the potential for personal change, they are also carriers of the potential for social change to the extent that social factors become visible in our dreams. They reveal the content of our social unconscious, that is, what we allow ourselves to remain unconscious of with regard to what is going on in society. Nazi Germany is an outstanding example. Much that was evil was going on at the time and gained expression in dreams. When the dreamer remains unaware of the message of the dream the opportunity for deeper social insight is lost. No room is left for any challenge to the social order. There is room only for personal demons and the transformation of social demons into personal demons. Dream consciousness may, indeed, pose a danger to a technologically supercharged, mechanically-oriented society.

The next extraordinary feature of our dreams is the connection of dreams to psi events. I am referring to the way we can play tricks with time while dreaming and pick up information about events that are spatially distant, and also play tricks with time that result in veridical precognitive visions. We seem to be more adept at this while dreaming than while awake. Here too, it has always been my impression, and it's only an impression, that psi effects are somehow related to the importance of maintaining our connectedness to our human and natural environment. Speaking from my experience, psi events are the surface outcropping of this underlying sense and need for unity, a kind of deeply hidden connective tissue available when other connective strategies fail.

Another quality of dreams that I think is under appreciated and has to do with the unusual features of dreams, (and this is truly speculative), is the connection of our dreams to survival, but not in the sense that we use the word survival in parapsychology. I do not refer to the survival of the self as an entity, but more concretely to the survival of the human species. This speculation derives from two aspects of my experience. One is the idea that dreams have to do with disconnects, from oneself and others. If we simply extend this idea to the broader range of disconnects, then, perhaps, dreams move us toward a more realistic assessment of the nature and depth of social disconnects that perpetuate the historically determined fragmentation that the human species has been subjected to down through the years. We've grown up differently in different cultures and different geographies evolved different races and so on. The species has been fragmented to the point where its survival as a species is at risk. I believe these are built into each of us, probably genetically, a concern with something larger than the self, namely, the preservation of the unity of the species. The second aspect of my experience that has brought me to this kind of thinking has been what I've learned in 20 years of working with people in dream-sharing groups. In many ways, this has completely undermined so many of the concepts I held and worked with as a practicing analyst. Dream-sharing when conducted with due respect to the problems a dreamer has in sharing a dream publicly, namely, how to approach a dreamer without being intrusive and seeing to it that the dreamer remains the gatekeeper of his or her own unconscious, a quality of connectedness emerges that embraces the dreamer, and the group. When this occurs there results, not only insight into a dream, but more importantly, a coming together and a deep sense of communion in the group.

Do dreams qualify as exceptional human experiences (EHE's)? I'll let you answer that question after I outline what I think is the essence of the dream. I will consider various points that Rhea White has suggested that qualify an experience as exceptional to see if the dream incorporates those characteristics. The first point emphasizes the spontaneity of exceptional human experiences, that one cannot make them happen. That fits the dream perfectly. No one, no matter how sophisticated they are with dreams and dream work, can determine in advance what the opening scene of a dream is going to be. It just comes at them. Second, the criterion of transcendence, to rise above, surpass, exceed, which seems to me to be precisely what happens when a dream moves us beyond the limits of the waking ego. It not only moves us into deeper parts of our psyche, but at times, transcends space and time. Third, it is a new experience of the self. We are more than we thought we were. This is typical of dreams. Dreams and dream work help us to realize we are more than we think we are. Fourth, they are all experiences of connections, which is the essence, in my opinion, of dream work. They rise out of this incorruptible core of our being that is sensitive to the needs of repairing and maintaining connections. Fifth, each is an experience of opening. Sixth, the spontaneous EHE comes during a state of heightened physiological and spiritual feeling, responding with one's whole self as one. Dreams occur during states of physiological arousal, psychological vigilance and, at times, have deeply spiritual overtones. Seventh, it's not a one-time experience, but occurs within an ongoing process and/or initiates a process. Again, that's exactly what dreams do. Dreams don't magically solve our problems, but if we allow ourselves to be confronted by them, the process goes on, and the next time we meet that problem with the boss, with authority, or whatever it is, we're in a better position, by virtue of the work done with dreams, to deal with that problem. Eighth, EHE's are potentially life-saving and significant. I have had experiences with dreams and dream work that have turned people around in a life-saving way. Ninth, the dreamer's allegiance to the truth of himself or herself has both scientific and spiritual implications. As I have said, dreams and dream sharing generate a sense of communion and bring us a bit closer to an idea that's been around a long time, the ideal of the brotherhood of man. Tenth, the importance of living the story out and telling it. Well, as far as dreams are concerned, this is essential, in my opinion, for the transformation of the healing potential of the dream, which occurred at night, into the actual waking social experience, through the support of others.

In conclusion, breaking the dream down as I have into the ordinary and the extraordinary and the quality of being an exceptional human experience results in distinctions that are implicit in the Western worldview. They are not distinctions made in so-called primitive cultures whose concerns encompass interest in the dream and include both the sacred and the profane. If we allowed them to do so, our dreams could help us sort out truth from falsehood at both a social and a personal level. As Bertrand Russell once noted, "the rational connects us, the irrational separates us," and it is in that sense that dreaming and dream sharing bring about rationality and connectedness into a highly irrational and disconnected world.

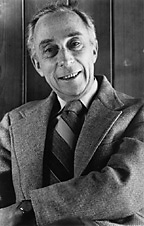

Dr. Montague Ullman is a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst internationally renowned for his work with dreams. In 1962 he founded the Dream Laboratory at the Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York. In the mid 1970s he resigned as Director of Psychiatry, Director of the Community Mental Health Center, and Director of the Division of Parapsychology and Psychophysics at Maimonides Medical Center to devote himself to dream research and group approaches to dream work. He is a past President of the American Society for Psychical Research, the Parapsychological Association, and the Society of Medical Psychoanalysts. Dr. Ullman is the author of numerous papers on theoretical and clinical studies of dreams and dreaming. He is the author and co-author of several books, including Dream Telepathy (McFarland, 1989), Working With Dreams (J.P. Tarcher, Inc. 1979), co-editor of The Variety of Dream Experience (Continuum Press, 1987), and co-editor of The Handbook of States of Consciousness (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986).